A home is one of the most significant architectural typologies that we experience throughout our lives. Largely serving as a significant private space, a home represents safety, ownership, and a sense of respite away from the rest of the world. It’s also historically been a place of routine, where we both begin and end our day, following the same patterns through different rooms of a home that we utilize. We can expect to sleep in our bedrooms, relax in a living room, cook in a kitchen, and eat in a dining room.

Despite the rigidity of purpose for each room, there’s something about a home that we cherish because of these standardized routines. But with new trends in technology, a shift towards an increasingly digitized world, and the abruptness of change brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, how might we reconsider what a home means, and how might we adopt their designs to newly learned behaviors? What if the root of housing comes from how we view and utilize a home at its foundational elements?

Lessons Learned About the Future of Home from the COVID-19 Pandemic

The pandemic that has consumed a majority of this past year has called us to question many things about the way that we live. Many of us have come to realize that the space which was once considered adequate for our daily needs in a pre-pandemic era now seems to feel less functional- especially if we live with others. The large shift to working from home, which is likely to stay even after COVID-19 has waned, will drive the need for more flexible and adaptable spaces. For instance, the dedicated home office which had fallen out of popularity in urban areas will now need to be recreated in a new way. This will go beyond the converted kitchen tables and couches that we’ve been working from and will become something more integrated, functional, and ergonomic to adapt to both the future of home and the future of work.

The pandemic has also shown us that outdoor space holds significant value. Not only the public parks, but the private balconies, backyards, and gardens which were once taken for granted have now offered an opportunity for fresh air, and time that can be spent away from the indoors.

Reconsidering Rooms That Make a Home

It’s also time that we reconsider what rooms that we currently are accustomed to that we can live without. Anna Puigjaner, a Spanish architect and winner of Harvard’s 2016 Wheelwright Prize, is a pioneer exploring the kitchenless home. Her idea builds upon the ideology of a shared economy, where a kitchen becomes a social outlet that forms a community within a building. While in the short term sharing a kitchen may be unfavorable due to the need to be in close contact with others, it is meant to support a long-term goal of creating healthy and sustainable housing, and also help reduce the amount of food that goes to waste. If we can consider removing something as critical to daily life as a kitchen from our home, what else might we be willing to share? Could we further push the boundaries and make the existing shared spaces of a home, including a living and dining room, even more public?

Rethinking Behaviors in a Home

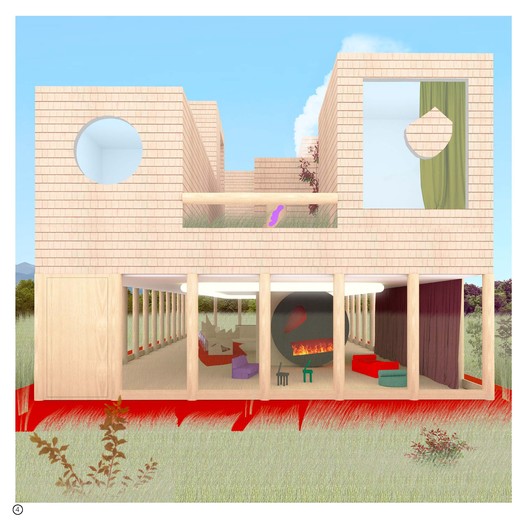

Recently hosted by Arch Out Loud, the HOME competition invited designers to explore ideas about domestic architecture for the future as it pertains to population shifts, new building techniques, as well as the rise of the co-living industry, smart houses, and even tiny homes. The results speculate on the variety of holistic ways that cultural changes can redefine how we live. One of the honorable mentions in the pragmatic category, The Home Alive, claims that the fundamental programmatic elements of homes today don’t reflect the way that we live and that the standard spaces don’t match the activities we perform. Proposing giving residents just a structural framework where panels and boards are interchangeable, rooms are able to be redefined into unique spatial qualities, ever adapting and ever-changing based on the needs of individual residents.

Another proposal, the overall competition winner, even considers expanding the traditional hours of the day spent doing various tasks. By tethering the time of the workday to the movement of the sun and the resulting shadows that are cast, the design of the home establishes a spatial and temporal separation between work and home labor, and questions the status quo of not only how a home is designed, but how and when we perform tasks within.

It's clear that how we define and design homes is an outdated process. Almost every other aspect of the built environment has been propelled into the 21st century in a way that matches the world's technological advancements and shifting needs of society. The way we live and the spaces we need have changed, and it's time to ask ourselves what a home truly is.

We invite you to check out ArchDaily's coverage related to COVID-19, read our tips and articles on Productivity When Working from Home and learn about technical recommendations for Healthy Design in your future projects. Also, remember to review the latest advice and information on COVID-19 from the World Health Organization (WHO) website.

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on